Media and User-Generated Content of Fear

Hamlet said one of the most memorable lines of all time, "To be, or not to be: that is the question." Shakespeare's ten simple words hooked into the audience's fear of uncertainty, life, and death.

Today, the hooks are deeper as we contemplate the same fears. Only this time, the lines are delivered via the media and amplified via technology.

Long gone are the days in which you can receive straightforward information about topics of interest in only one newspaper, one news channel or radio station. Instead, mines of clickbait are laid out everywhere on our phones, laptops, TV news, newspapers and radio stations. Content publishers are just waiting for us to step on one.

Frankly, a more accurate analogy is not of land mines but mousetraps. For every finger pointed at "the media" for fear marketing, we forget to consider the three pointing back at us. Mousetraps only work because mice love cheese. Fear works because we are drawn to it.

From the daily news, Trump tweets, to Narcos on Netflix, we're obsessed with crime and negativity. To understand why fear grabs our attention, we need to dive into the neuroscience of fear and perception.

Our Brain on Crime

Perception is reality. Neuroscientists know how true a statement that is. Fear gains its psychological power through its ability to trump perception over reality.

Here's our perception. Our neighborhoods feel more unsafe, our cities more dangerous, our economies more unstable. And our governments more precarious.

Here's our reality. In the US, violent crimes have halved over the past quarter-century. Today, more people die from sugar than terrorism, homicide, and road accidents combined. The US crime rate is at the lowest it has ever been. Yet, most Americans still believe that crime rates are increasing.

Why the difference? Evolutionary biologists point at our outdated fight-or-flight mechanism. Our brains are programmed to pay extra attention to perceived threats and, in turn, make snap judgments. There is no room for careful reasoning when facing a lion. Fight or flight are the only options.

Today, we no longer face the threat of real lions, and yet continue to pay extra attention to perceived threats and react in a binary, fight-or-flight manner.

This still does not explain why emotion trumps statistics, why the headlines, stories, and graphic images of negative events usually overrule reality and facts. The reason: our brain is flat-out biased. The brain is biased towards easily-recallable events. It loves things that come readily to mind. If items are easy to recall, they must be true, or so the brain thinks. Neuroscientists call this the availability bias.

When trending news about current events come to mind, this is the availability bias in action. It explains why we believe the events we often see and hear are more representative of the reality we face than actually the case. Social media is littered with horror stories which, over time, become the most readily available form of data our brain uses to calculate our reality.

The availability bias also explains why we tend to neglect how life-threatening some of the ordinary events are. Accidentally running a red light, for example, has resulted in 11 times more deaths in the US in 2016 than terrorism.

Availability bias is multiplied by yet another bias. Research shows we pay more attention to and remember bad news. This aversion to good news is called the negativity bias. Our brains are especially reactive to words with negative connotations such as "bomb" and "war," while they don't respond as well to words with positive connotations such as "baby" and "smile.” Statistics only make things worse. Simply put, it is easier to comprehend and accept emotional messages than it is to focus on energy-consuming statistics.

The strategy of fear-inducing news works like this: if it bleeds, it leads. A prime example is the story of a doctor who returned from West Africa in 2014 with the Ebola virus. He became the most notorious man in the US overnight. Despite being quarantine long before posing a health risk to anyone, the media exploded with breaking news, causing flight cancellations and school closings in the process.

If it bleeds, it leads. For better or worse, fear is the silent big-seller.

User-Generated Content (of Fear)

Hyperlocal apps like Amazon Ring's Neighbor, Citizen, and Nextdoor are designed for users to view local crimes in their neighborhood and chat about them in real-time. The trend far surpasses Facebook as a firehose of availability and negativity biases. It is as if fear created by media wasn't enough that we had to create our own. Hyperlocal apps are ushering a period of user-generated fear content.

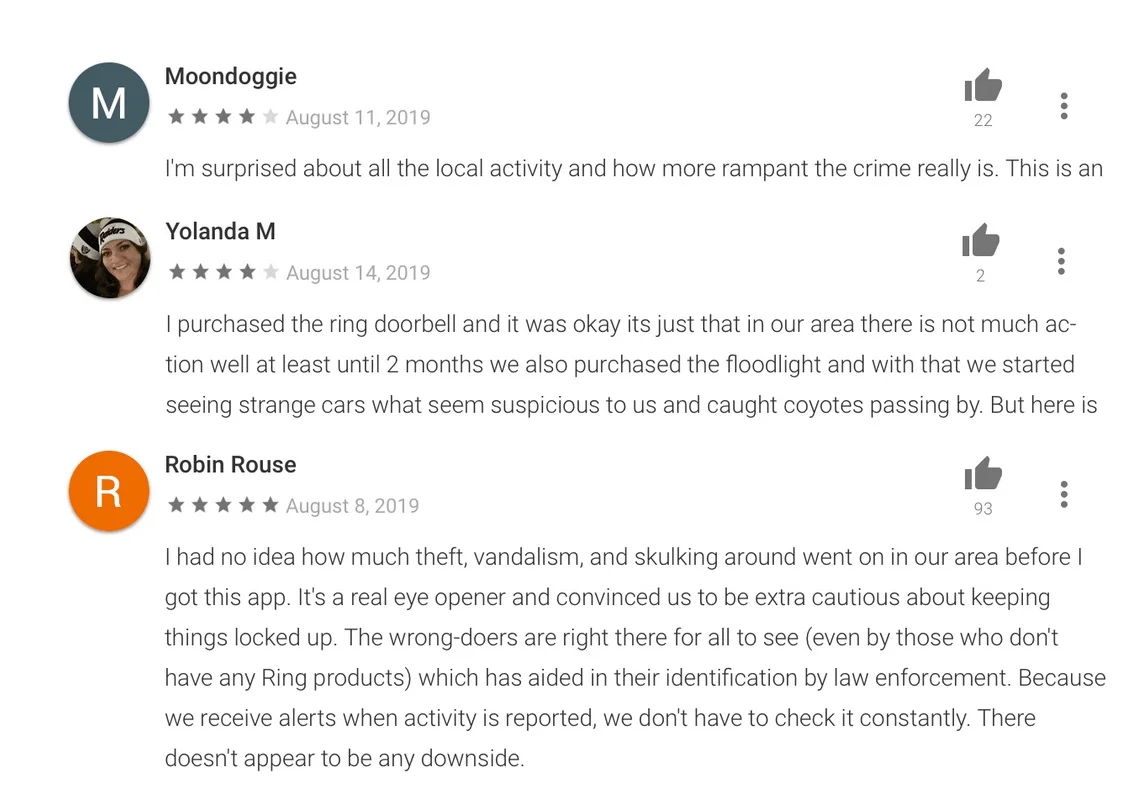

App reviews reflect the users' state of mind. People weren't even aware of "suspicious cars" driving by, or how "rampant the crime really is" before jumping on these apps.

Source: User Reviews for Ring’s Neighbor from the Android’s Store Google Play

Nextdoor is the 9th most downloaded social app in April 2019, up from being the 27th a year prior. Citizen is the 7th most downloaded, and Amazon Ring's Neighbor is the 36th most downloaded social app, up from 115th.

Wherever users go, investment follows. Ring's Neighbor raised over $209 million in investment before being purchased by Amazon for a staggering total of $1 billion.

Fear-based content is likely to rise, only this time, caught on Ring cameras, shared on Citizen and reported by outlets on Facebook.

With all that in mind, the question is what to do when standing face-to-face with the fear-content wave? One, realize this is not a lion but mainly the perception of one. Next, mind the fight-or-flight reaction. Lastly, beware of the availability and negativity biases which make us vulnerable to the 'if it bleeds, it leads' hack.

It helps to make fear less of a reaction, and more of a choice. To paraphrase Hamlet, “To fear or not to fear: that is the real question.”

What’s Next?

References

De Waal, A. (n.d.). Sudan: 1985 – 2005. Retrieved from https://sites.tufts.edu/atrocityendings/2015/08/07/sudan-2nd-civil-war-darfur/#Fatalities

Forbes: Deaths in Red-Light Running Crashes are on the Rise; New Guidelines Released, Tanya Mohn

Gallup: Most Americans Still See Crime Up Over Last Year, Justin McCarthy

Global Terrorism Database. (2017). American Deaths in Terrorist Attacks, 1995 - 2016. Retrieved from https://www.start.umd.edu/pubs/START_AmericanTerrorismDeaths_FactSheet_Nov2017.pdf

Judgement and Decision Making, vol 2, no. 2: “If I Look at The Masses I Will Never Act” Psychic Numbing and Genocide, Paul Slovic

National Consortium for the Study of Terrorism and the Responses to Terrorism (START): American Deaths in Terrorist Attacks 1995 - 2016, Dr. Erin Miller & Dr. Michael Jensen

New York Times: Experts Oppose Ebola Travel Ban, Saying it Would Cut Off Worst-Hit Countries, Jad Mouawad

Our World In Data: Is It Fair to Compare Terrorism and Disaster with other Causes of Death?, Hannah Ritchie

Pew Research Center: 5 Facts about Crime in the U.S., John Gramlich

Psychology Today: If it Bleeds, it Leads: Understanding Fear-Based Media, Deborah Serani Psy.D

Slovic, P. (2007, April 2). "If I look at the mass I will never act": Psychic numbing and genocide. Retrieved from http://journal.sjdm.org/7303a/jdm7303a.htm

UCR Publications. (2018, September 10). Retrieved from https://www.fbi.gov/services/cjis/ucr/publications#Crime-in-the-U.S

Universal Crime Reportings (UCR Publications): Crime in The United States 1990 - 2018, Federal Bureau of Investigations

Vox: Fear-based Social Media like Nextdoor, Citizen, and now Amazon’s Neighbor, Rani Molla

World Peace Organisation: Sudan 1985 - 2005, Alex de Waal

Dive into the fascinating intersection of psychology and marketing and how to use psychological biases in marketing strategy.