The Psychology of Curiosity and Its Influence on Met Gala Fashion

Photo by Flaunter, Unsplash

Remember Lady GaGa’s Met Gala meat dress? Think back to it.

Would you ever be caught dead wearing such an outfit? Perhaps not. Then why was the world so enamored and beguiled by such a creation? We’ll answer this by looking inwards at the way the brain works.

Every year, on the first Monday of May, the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City is transformed to host one of the most anticipated events in fashion—The Met Gala.

The events leading up to and following this glamorous fundraiser are often as exciting as the Gala itself. The most intriguing part is the announcement of the year’s theme, which sends A-list celebrities, stylists, and fashion designers into a frenzy trying to create sensational fashion ensembles. But the frenzy doesn’t stop there. The media, especially social media, is flooded with reviews, critiques, photographs, and emulations of the red carpet creations for many days, and for some iconic looks, even years.

Given how over-the-top and extravagant the looks are, the buzz and curiosity around outfits most people will never buy, wear or even look at, is certainly puzzling. So, why are we so curious about—and sometimes enamored by—fashion ensembles we’ll never wear? The answer, as you’ll find out, lies in the way our brain is wired.

The Psychology and Evolution of Curiosity

One of the longstanding common threads in driving human behavior is curiosity. Take a look at humanity’s progression (and regression) and you’ll realize how ubiquitous curiosity is. From Eve’s apple, Pandora’s box, and Galileo’s explorations to today’s scientific discoveries, murder mysteries, and reality TV obsession; curiosity is unfaltering. And it’s an aspect of human behavior that has long been researched. Let’s rewind for a bit.

Back in 1890, English psychologist, William James, described two types of curiosity. The first is an instinctual or emotional response to something new and exciting like a toddler being fascinated by a box of slime, while the other is a more human-specific scientific curiosity to learn more and fill a gap in knowledge like writing a graduate-level thesis paper.

Fast forward 64 years later, psychologist Daniel Berlyne built on this and created the Theory of Human Curiosity, calling the two types of curiosity diversive curiosity and specific curiosity. Diversive curiosity is the general tendency of an individual to seek novelty, take risks, and search for adventure, while specific curiosity is the tendency to investigate a specific object or problem to understand it better. He also studied the kind of stimuli that would generate either form of curiosity and found that objects that are complex, novel, uncertain, or conflicting prompt curiosity.

Finally, Berlyne’s colleague, H. I. Day formalized this and described such stimuli as falling under the Zone of Curiosity, whereby stimuli manage to stimulate and calm the brain, are exciting but in a manageable way, and create risk amidst comfortability.

The Zone of Curiosity can be applied to the ways in which horror films are made and written. Stephen King, author of famous horror movies ‘The Shining’ and ‘It’, artfully weaves in the marriage of curiosity and satisfaction in his writing. His characters, Pennywise (the clown from It) and Jack Torrance (from The Shining) are human beings (zone of relaxation) who behave in peculiar ways (zone of anxiety) leaving the audience at the edge of their seats (zone of curiosity). As King once said, “Although curiosity killed the cat, satisfaction brought the beast back.”

Beyond the film industry, curiosity plays a big role in modern-day marketing as well. Here’s how it drives consumer behavior.

How the Psychology of Curiosity Plays a Role in Marketing and Consumer Behavior

To make more sense of what drives curiosity, the Information-Gap Theory was introduced in the early 90s. In essence, it’s the gap between what you know, and what you need to know in order to make a responsible decision. Here’s an analogy:

Imagine you’re standing at the edge of a cliff, contemplating whether to jump across the valley so you can take in the beautiful scenery on the opposite side. Naturally, if the gap between the cliff and the valley is too far, it’s daunting. But it’s near, it’s not interesting enough to make the jump, because you can see the other side from where you’re standing.

Knowledge works in similar ways. We strive to close the knowledge gap between the known and the unknown. As we have learned from the story of Goldilocks and the Three Bears, the gap can’t be too small or large. Like many things, it needs to be just right. Small gaps aren’t worth the effort, while too large of a gap can make putting in the effort an overwhelming task. To generate the right amount of curiosity for consumers, marketers should create a manageable and exciting knowledge gap.

Neuromarketers can harness this framework and artfully create gaps for consumers to engage with. One proven effective strategy would be to evoke curiosity by showing consumers the gap in their knowledge, provide piece-meal information that they can chew on to resolve their curiosity, and give them time to digest the curiosity—which they must do on their own.

In the context of marketing, a good advertisement is one that grabs attention by providing a little bit of information, then creates a scenario to make the consumer aware of how much they don’t know as opposed to how much they already know. Until finally, it introduces a call to action to help consumers fill their information gap on their own.

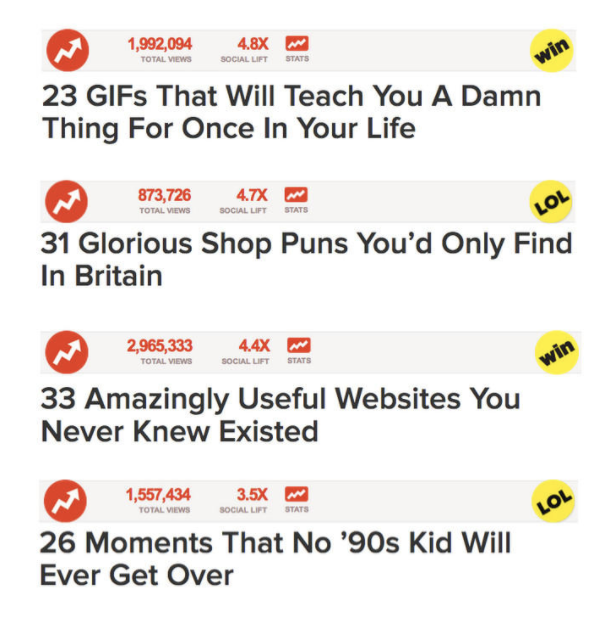

Brands have already begun adopting this technique. BuzzFeed advertising is amazing at it.

These innovative and catchy titles prime the audience as to what they would get by clicking on the quiz. Hence, they form an information gap between the known and the unknown and compel users to respond to the call to action by clicking on the ad. Back in 2016, Buzzfeed content received ~6 billion monthly views and their audience spent ~100 million hours per month viewing Buzzfeed content! Due to their evolving expertise in creating and advertising knowledge gaps, we can conservatively speculate that these numbers have at least doubled. Now, let’s circle back to the Met Gala.

How Curiosity Influences the Met Gala and Fashion Industry

Now that you know the psychology and marketing of curiosity, it’s easier to understand the fascination behind what could be the next big thing in fashion.

Met Gala fashion has found its place in the zone of curiosity–it doesn’t feature familiar, everyday clothes and hence, removed from the zone of relaxation. At the same time, it features clothes that, at the end of the day, are worn by human beings, which removes them from the zone of anxiety.

More specifically, the Gala introduces the theme weeks, if not months, before the event which peaks and grabs people’s attention by generating curiosity. This element of anticipation urges people to tune into the event to close their knowledge gap. In recent years, marketers and social media influencers have also harnessed this Met Gala-induced curiosity to market their own pages and products, giving rise to the “best-dressed” and “worst-dressed” lists that swarm the internet post-event.

The gap between everyday fashion and Met Gala fashion is manageable and exciting. It’s fashion that pushes the envelope in a believable way and that’s why the Met Gala is the fashion industry’s most anticipated event of the year.

Now we really know why the buzz around Lady GaGa’s meat dress in the VMAs makes sense.

What’s Next?

References

Berlyne, D. E. (1954). A theory of human curiosity. British Journal of Psychology, 45(3), 180. (https://search.proquest.com/docview/1293487384)

Buzzfeed: How Buzzfeed thinks about Data, and Some Charts, too, Dao Nguyen, 2019

Day, H. I. (1971). The measurement of specific curiosity. In H. I. Day, D. E. Berlyne & D. E. Hunt (Eds.), Intrinsic motivation: A new direction in education. Ontario: Ontario Institute for Studies in Education.

Good Reads, Stephen King Quotes (Quote 481536) (https://www.goodreads.com/quotes/481536-and-didn-t-they-say-that-although-curiosity-killed-the-cat)

James, W. (1890). The principles of psychology New York. Holt and company. (http://psychclassics.yorku.ca/James/Principles/prin24.htm)

Loewenstein, G. (1994). The psychology of curiosity: A review and reinterpretation. Psychological bulletin, 116(1), 75.

Menon, S., & Soman, D. (2002). Managing the power of curiosity for effective web advertising strategies. Journal of Advertising, 31(3), 1-14.

WordStream: 6 Ways to use the Curiosity Gap in your Marketing Campaigns, Dan Shewan, 2017

Dive into the fascinating intersection of psychology and marketing and how to use psychological biases in marketing strategy.