Who Hoards? Panic Buying, Consumer Behavior, and the Personality of Stockpiling During COVID-19

Photo by Jasmin Sessler, Unsplash

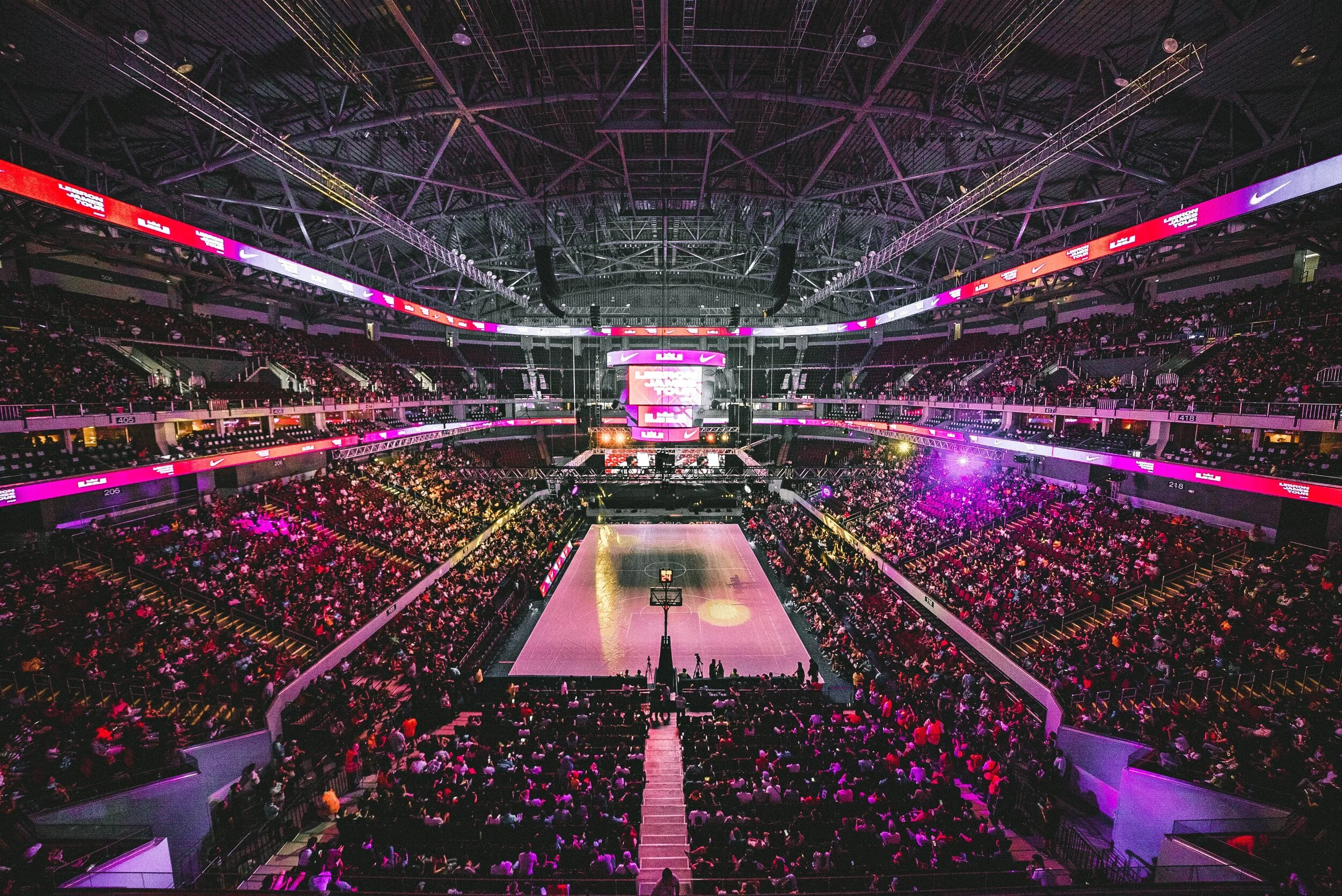

Across the globe, shelter-in-place orders have been met with mad dashes to the store. Each news cycle seems to bring in fresh stories of extreme stockpiling and worryingly sparse shelves.

While stories like these likely lead us to overestimate the actual rates of hoarding, where it does exist, it represents a serious issue. Indeed, this behavior has brought significant concern about supply shortages.

Understanding stockpiling behavior has become increasingly important, as it presents the possibility of a Tragedy of the Commons type of dilemma: if everyone acts in their own self-interest, and assumes others will do the same, the community as a whole may suffer.

This question is particularly relevant to social psychologists. How do people navigate the inner conflict between personal and societal interests? Do different people approach this differently?

Put simply, who hoards?

Personality Science Meets Consuming Behavior

New research suggests that not everyone is equally likely to engage in stockpiling behavior. These insights come from Simon Columbus, PhD student in the Department of Experimental and Applied Psychology at Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam. His new pre-print suggests that one’s personality makes an important contribution.

"Economists have thought about this as a coordination game, like a bank run. I was interested whether personality plays a role in this context.", Columbus says.

Previous work on personality and hoarding behavior which is based primarily on hypothetical scenarios. In contrast, Columbus' new work was done amid the coronavirus pandemic itself, providing a rare, direct glimpse into the relationship of personality and stockpiling behavior.

Across two studies, Columbus found that people who were high in Honesty-Humility were more likely to refrain from stockpiling. This personality dimension is closely associated with prosocial behavior, trust in others, and the tendency to look out for others. In other words, these are the “good folks”.

That this personality trait would be inversely related to stockpiling isn’t overly surprising. What was surprising was the observation stockpiling behavior was not mediated by the belief that others will do the same. As Columbus puts it, “This suggests that people who refrain from stockpiling do so with a knowledge that this may come at a personal cost.”

All told, these findings suggest that refraining from stockpiling is closely associated with an altruistic disposition.

Altruism, Situational Factors, and Curbing Stockpiling Behavior

Clearly then, if we want to curb stockpiling behavior, all we need to do is to increase everyone’s level of altruism. Easy right? As lovely as that might sound, the evidence suggests that Humility-Honesty, like most personality traits, is relatively resistant to change.

People do tend to become a bit nicer and altruistic as they get older, but this, of course, won't curb stockpiling anytime soon. What will?

"We also need to look at the situational factors at play in these behaviors, which allow these dispositions to be expressed in the first place", Columbus encourages. He suggests looking more in-depth at the definition of Honesty-Humility, and the situational factors which encase it.

This definition of Honesty-Humility comes from Ashton and Lee, who write:

"Honesty-Humility represents the tendency to be fair and genuine in dealing with others, in the sense of cooperating with others even when one might exploit them without suffering retaliation."

Or, as Columbus summarizes, "The tendency NOT to exploit, even if you could get away with it.”

The degree to which the behavior is exploitative (e.g., potentially leading to shortages) is largely out of our control. Curbing stockpiling behavior then primarily comes down to creating systems where others can’t easily get away with it.

The most prominent of such deterrents take two forms:

Financial Penalty

One strategy here has been creating a very unorthodox pricing structure to directly de-incentivize bulk purchases.

A small supermarket popularized this in Denmark named Rotunden. To curb the hoarding of hand sanitizer, they priced the first at a very reasonable kr40 ($6). Any bottles beyond this first one? That’ll cost you Kr1000 ($147) each. This sharp rise in pricing has seemed to cool the hoarding of this otherwise hot commodity.

Social Penalty

Another key strategy here is the application of a social penalty. Enter the world of social shaming. And here, we may all have a natural inclination for this already. Stephanie D. Preston, Professor of Psychology at the University of Michigan suggests that engaging in social shaming is an evolved adaptation.

As she recently wrote in The Conversation, “As a social species, human beings thrive when they work together, and have employed shaming – even punishment – for millennia to ensure that everyone acts in the best interest of the group.” Shaming comes naturally, especially in times of potential scarcity.

In the age of social media, social shaming is especially potent. She points to the recent example of Matt Colvin, a young man from Tennessee who bought nearly 18,000 bottles of hand sanitizer in the hopes of selling each at a premium. Due to the swift backlash on Twitter, he ended up donating all of it.

Equally important, his story serves as a cautionary tale for others who may have considered similar tactics.

——

Stockpiling behavior presents a unique window into the human psyche. Especially in regions where supply shortages are genuine concerns, it forces the individual to grapple with a direct conflict between individual and communal interests.

Different people navigate this conflict differently. At the same time, regardless of personal dispositions, the introduction of simple deterrents goes a long way in stemming this behavior.

As Columbus describes, “Situational factors prevent these dimensions of personality to be expressed in terms of overt behavior”

Altruistic orientations play a role in stemming stockpiling behavior. But the “good folks” can’t do it all themselves.

Written by Matt Johnson, PhD

Published by Prince Ghuman

What’s Next?

References

Ashton, M. C., & Lee, K. (2007). Empirical, theoretical, and practical advantages of the HEXACO model of personality structure. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 11(2), 150–166. (pg. 156)

Columbus, S. (2020, March 24). Who Hoards? Honesty-Humility and Behavioural Responses to the 2019/20 Coronavirus Pandemic. https://doi.org/10.31234/osf.io/8e62v

Corkery, M., & Maheshwari, S. (2020, mar). Is There Really a Toilet Paper Shortage? Retrieved from https://www.nytimes.com/2020/03/13/business/ toilet-paper-shortage.html

Fetterman, A. K., Rutjens, B. T., Landkammer, F., & Wilkowski, B. M. (2019). On Post-apocalyptic and Doomsday Prepping Beliefs: A New Measure, its Correlates, and the Motivation to Prep. European Journal of Personality, 33(4), 506–525.

Interview with Simon Columbus via Zoom (March 27th, 2020)

Miller, A. (2020, Mar). Shoppers stockpile supplies as sellers price gouge amid coronavirus outbreak (Video), CNBC

Nicas, J. (March 2020) The Man With 17,700 Bottles of Hand Sanitizer Just Donated Them, The New York Times

Pletzer, J. L., Balliet, D., Joireman, J. A., Kuhlman, D. M., Voelpel, S. C., & van Knippenberg, D. (2018). Social Value Orientation, Expectations, and Cooperation in Social Dilemmas: A Meta-analysis. European Journal of Personality, 32(1), 62–83.

Preston, S. (March, 2020) Your brain evolved to hoard supplies and shame others for doing the same. The Conversation

Soto, C. J., John, O. P., Gosling, S. D., & Potter, J. (2011). Age differences in personality traits from 10 to 65: Big Five domains and facets in a large cross-sectional sample. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 100(2), 330–348.

Thielmann, I., & Hilbig, B. E. (2014). Trust in me, trust in you: A social projection account of the link between personality, cooperativeness, and trustworthiness expectations. Journal of Research in Personality, 50(1), 61–65.

Dive into the fascinating intersection of psychology and marketing and how to use psychological biases in marketing strategy.