How Pandemics Fuel Cognitive Biases

Photo by visuals, Unsplash

Since the 2014 Ebola outbreak wasn’t enough of a warning to humanity, Bill Gates got on stage in 2015 to deliver a powerful message. The key takeaway was in the title, glaring at us: The Next Outbreak? We’re Not Ready.

As parts of the world go on lockdown and extroverts realize how their counterparts spend life indoors, the communicable spread of misinformation through social media and the web becomes a matter of life and death. People struggle to differentiate news between noise. If we had lived in a world not deluged by irrelevant and inaccurate information, then we may have responded to Gates’ wake up call differently.

In unique circumstances such as COVID-19, the general public must understand—not misunderstand—the facts as they stand. Turns out, the brain is vulnerable to noise, specifically the most recent noise reported.

While many struggle to draw the line between fact and fiction, the lack of data on COVID-19 has not only made it difficult for health officials to control the spread of the disease itself, but also the false rumors, which infect the public’s minds.

To understand why we naturally recall recent stories over statistics, let's look into the psychology behind why misunderstandings spread rapidly in the first place.

COVID-19 and Cognitive Bias

As we’ve learned in media and user-generated content of fear, our brains are programmed to pay extra attention to perceived threats and, in turn, make snap judgments. This is what evolutionary biologists call the (outdated) fight-or-flight response system. It’s outdated because we face global pandemics, climate catastrophes, but not lions to run away from on a daily basis. In times of the COVID-19 crisis, we can’t afford to make snap judgments, let alone the world. But because our brains are biased towards easily-recallable events, we do.

Neuroscientists call this the availability bias. It explains why we’re attached to anything that comes readily available to the mind. For example, say your parents saw a video on Facebook shared by family friends about a home burglary in the city one night. On a call, while catching up, you randomly mention that one of your friends had a break-in recently. Although break-ins are statistically on the decline due to user-friendly alarm systems and a generally more peaceful country, Mom and Dad can’t help but put two and two together. The availability bias makes the brain choose stories over statistics. And the same happened with the novel COVID-19.

When the world first heard about the disease, panic and misinformation—the rush to buy as many toilet paper rolls, the patronizing comparison to the flu, and the never-ending news about stockpiling groceries—made it difficult for the public to stay calm and indoors. Enter availability bias.

During the crisis, a study of 100,000 participants in the UK found that very few were engaging in traditional stockpiling and shoppers would simply frequent stores to restock. But because of the pandemic crisis, there were an extra 15 million trips to the grocery store in just one week alone. The availability bias presses the go-getter panic button in many of us.

Though several governments address public safety directly by educating its citizens and refuting rumors, some lean on to dictatorial, discriminating actions. US President Donald Trump called the coronavirus the ‘Chinese virus’ for political reasons. As a result, health officials have to disprove claims alongside caring for the ill. While on the other side of the world, Philippine President Rodrigo Duterte deals with hungry quarantine violators by ordering the police to ‘shoot them dead’. Not only do governments fight against the availability bias, but also brands in the consumer world.

The Impact of the Availability Bias on Consumer Behavior

If there was one brand that knew they were up against something big from the first day the virus hit the news, it’s Corona beer. Following the outbreak, a survey polled more than 700 adults and found 38% would no longer buy Corona “under any circumstances.”

In relation to availability bias, if you were asked what comes to mind when you hear ‘Corona’ before the pandemic, chances are you’d say beer and perhaps imagine the beach. (That’s no coincidence, really. They spend $100 million on annual marketing campaigns to maintain this association). But if asked today, you can’t help but think of the coronavirus. When our brains succumb to knee-jerk reactions like this, the bias is deep at work.

Since the spread of the virus, the beer brand has lost over $170 million in earnings in China alone—gone are the millions spent on reaffirming its beach ethos, pretty much. There’s no way to foresee a pandemic of this nature. Corona beer simply got the unlucky draw. Now, speaking of the beach...

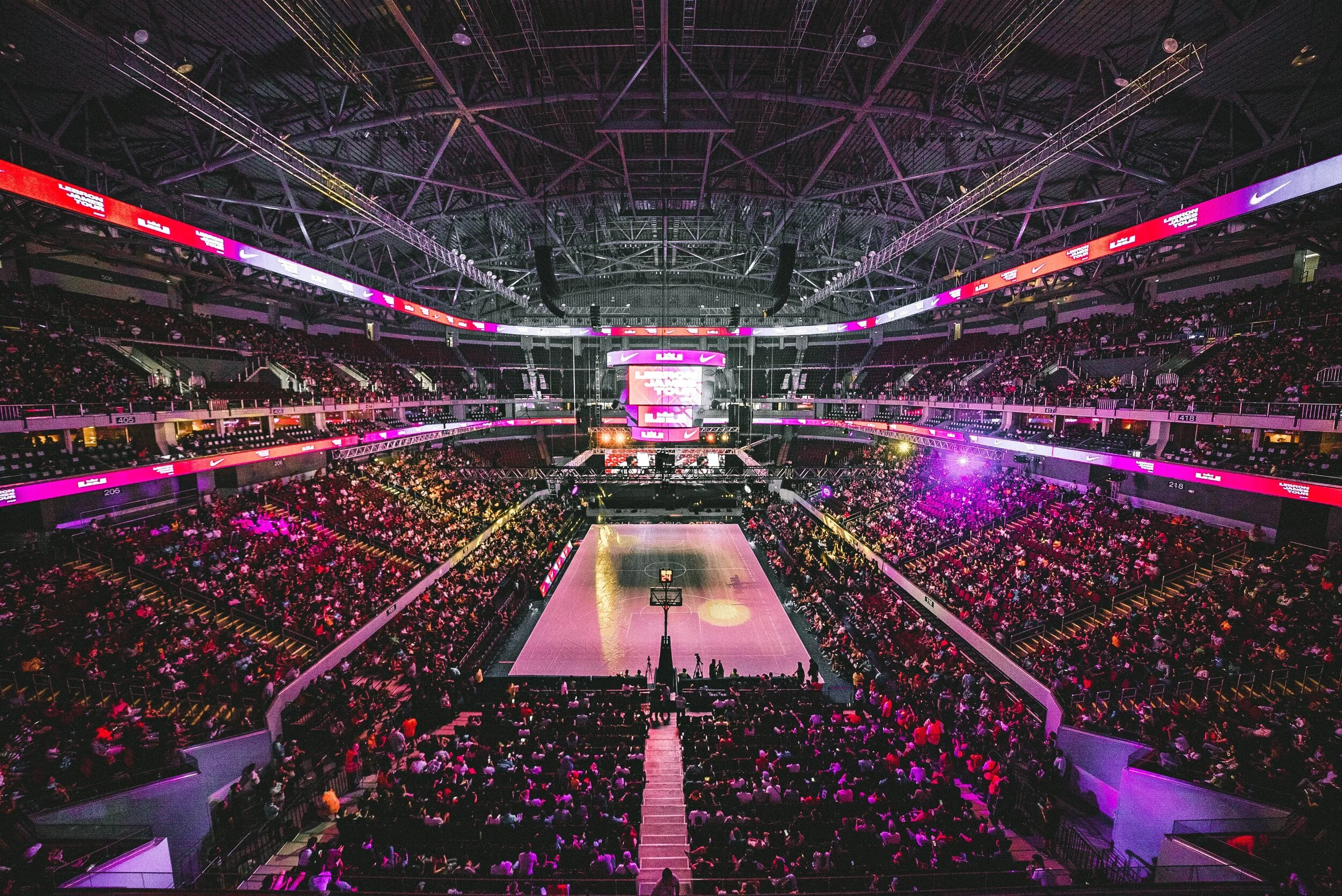

How the Availability Bias Played a Role in Spring Break

While many spend time locked up indoors drooling at the pictures of when they were allowed to go outside, others take a more laid-back approach to social distancing—by not social distancing at all! Why did people still go out for Spring Break? The short answer: Fear of missing out coupled with the availability bias had driven college kids to party.

The long answer: vast victims of the insidious bias believed the virus hasn’t done any harm to young adults but more so to the elderly, therefore the situation has most likely improved—or so they thought. Though the number of cases remains on the rise in the US as of this writing, a Spring Breaker’s brain had an inaccurate sense of safety. “If everyone my age is out having a fun time, why should I worry?” they rationalized.

Videos of rebellious teenagers in Miami beach brushing off the threat of a global pandemic have gone viral online. One student justified himself by saying “If I get corona, I get corona, at the end of the day I’m not gonna let it stop me from partying.”

Here planted the most recent image: Ostensibly healthy young adults hanging out on beaches. Here’s the bias at work: How can partying it up in Spring Break 2020 be a bad thing when the beach, booze, and bad behavior are the first things that come to mind?

This imagery, through the availability bias lens, implanted an overly sanguine impression of the pandemic, which adds more trouble on top of the struggle to flatten and crush the curve.

Misinformation is a disease for the mind, and clarity is power. If there was ever an alternative title to a talk addressing future global pandemics, it could be this: The Next Outbreak? We’re Ready, Availability Bias.

What’s Next?

References

Barrons: Americans Say They Won’t Drink Corona Beer Because of Coronavirus. Sales Are Up 5% Anyway, Al Root

CNN: Yes, of course Donald Trump is calling coronavirus the 'China virus' for political reasons, Chris Cillizza

ConsumerReports: Fight Against Coronavirus Misinformation Shows What Big Tech Can Do When It Really Tries, Kaveh Waddell

DenverPost: Do we really need to remind you that you can’t catch coronavirus from drinking Corona? Apparently, we do, Tiney Ricciardi

Forbes: Despite The Fear Mongering, We Will Overcome The Coronavirus, Jack Kelly

Independent: CORONAVIRUS: OWNERS OF CORONA REPORT £132M LOSS FOLLOWING OUTBREAK, Olivia Petter

MarketingWeek: ‘Accidental’ stockpilers driving shelf shortages, Ellen Hammett

Mediaradar: Corona Advertiser Profile

NBC: Threat of Coronavirus Causing ‘Overbuying Epidemic’ at Local Stores, Dave Summers

Reuters: 'Shoot them dead' - Philippine leader says won't tolerate lockdown violators, Martin Petty

TED Talk: The next outbreak? We’re not ready, Bill Gates

TheGuardian: 'If I get corona, I get corona': the Americans who wish they'd taken Covid-19 seriously, Poppy Noor

WashingtonExaminer: Nunes says 'media and the Left' throwing the public into 'panic' over coronavirus, Emma Colton

Dive into the fascinating intersection of psychology and marketing and how to use psychological biases in marketing strategy.